Disco Elysium Review

Disco Elysium doesn’t think very highly of people. Or existence. There’s a general pessimism that’s inherent to the game and based on the interviews I’ve read with lead writer and designer, Robert Kurvitz, that seems to track with his general view on the world. Born in Estonia, Kurvitz has acknowledged the influence of Soviet literature, specifically Soviet science fiction, on his work and I couldn’t argue. Disco Elysium is an angry game, a morbid game. It feels like watching a car-wreck take place before your eyes and then having to help with the clean-up. It made me terribly uncomfortable and challenged my world view. It’s a fascinating game, though I’d argue that it tends to fall a little in love with itself at times, spewing heaps and heaps of information at you until you find yourself skimming detailed histories, trying to remember names and places like you’re cramming for a history exam. As someone who loves history, there are worse things, but there’s no arguing that Disco Elysium is a dense game and it’s bound to turn some people off.

You begin the game in darkness, waking up from a terrible hangover, a hangover so bad that it causes the player character to suffer amnesia so powerful they can’t remember anything, anyone, or any place. It’s hard to get into the details because simply discovering the premise of Disco Elysium feels satisfying. The game offers so little information upfront, just learning your name is a bit of a challenge. The spoiler-free summary is that while recovering from your amnesia, you meet a fellow police officer from another precinct, Kim Kitsuragi. Kitsuragi tells you that he’s been sent to help investigate a murder that you’ve been putting off while on a three-day drunken bender.

The story and mystery is everything in Disco Elysium, and mysteries abound. One mystery is simply trying to discover who you were before losing your memory. You struggle to recall your name, your past, and why you have this addiction to cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs. To say the hero of the story is down on their luck is an understatement; the player character is a walking disaster. While you can make choices and change your character’s future, their past is set in stone, and Disco Elysium pushes you toward substance abuse and terrible life choices. You can try to keep things on the straight and narrow, but even then you still have to contend with your monstrous background. It almost makes the game unplayable, making the hero be so despicable, but having Kitsuragi hang around as your moral compass and party buzz-kill not only helps keep you rooting for the hero but creates a fun buddy-cop dynamic. Again, based on how you play the characterizations can change, but it’s an absolute blast creating your own Holmes/Watson dynamic.

The second mystery is the murder you and Kitsuragi solve together and it’s a good one. I need good pay off in a mystery story and Kurvitz is able to weave a web of clues and facts that make the reveal not only satisfying but thematically in-keeping with the narrative. When the curtain is pulled back and the killer is revealed, I felt disgusted, angry, and sympathetic. While Disco Elysium doesn’t think very highly of people, it becomes a parable about what happens when our anger and pain consume us. While the narrative takes a bit to get going, it’s highlighted by some great moments, including a violent climax that I won’t soon forget.

My biggest criticism of Disco Elysium is that it’s dense as a history book. You amnesia prevents you from recounting any of the history or politics of the world and the game may be a little over-eager to explain them to you. While I appreciate the developers’ desire to have a deep and fully realized world, I still felt my eyes glaze over as the game tried to explain the current political climate and histories that other games usually relegate to a codex. These details are somewhat essential to the story, so I understand the fear of players missing some of the context, but the game needs to trust players to figure it out.

There’s a lot of subtext in the world of Disco Elysium. While the cRPG aesthetic is largely played out at this point, developers ZA/UM created a world that’s visually reminiscent of Eastern Europe, particularly the Baltic nations like Kurvitz’s native Estonia. The game is set in the slums district of Martinaise, filled with concrete and symbols of industrialization. Beneath the grey of cement and steel, there’s a rich history of an opulent aristocracy and the revolution that dethroned them. Military bunkers lie abandoned, apartment complexes have been neglected – in a city that has seen its fair share of war, this little corner has never recovered. It’s brown and washed out, but that’s intentional. The design of the world isn’t going to give you a new wallpaper for your computer, but it certainly is evocative in its own way.

The audio design is where you can feel the constraints of the budget. The different areas of the world each have some ambient music that repeats upon each visit. It’s all serviceable, but I couldn’t praise it more than that. The voice-acting is definitely a weak point, though it’s mercifully incomplete so you only have to hear a handful of line readings before it cuts out and you’re left to just read the text. There are also moments where some sound design has been added to enhance the text, but it’s usually jarring and strange since the game is typically quiet. It doesn’t really work.

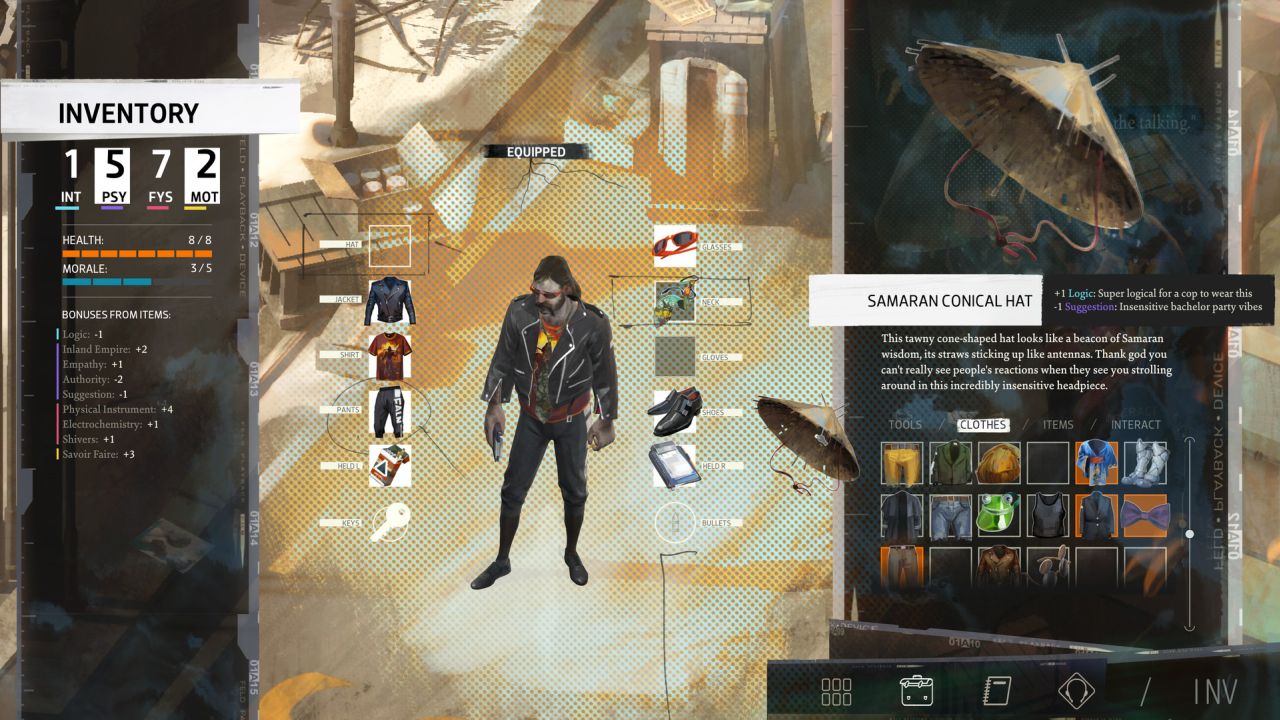

Since the return of the cRPG, the genre has been trying to figure out how to navigate combat, but ZA/UM has decided to simply do away with it. And that’s probably for the best as it allows the narrative to play out more naturally without shoehorning in dungeons and monsters. Thus, the mechanics of Disco Elysium are obsessed with your detective skills. There are twenty-four skills for your character and they can be min/maxed as you’d like. This freedom allows you a lot of creativity in what your character can do. You can play as a Sherlock Holmes, using intelligence and logic as your weapons, but coming up short when you have to get physical or interact with people. You can play brawling psycho degenerate like Mel Gibson’s character in Lethal Weapon. Or mix and match as you’d like.

ZA/UM is excellent at making use of all twenty-four skills. While you explore and interact with the world, these skills act as characters, inserting themselves into the dialogue, informing you about the clues you can see or hear. A skill like “Perception” might help with notice that a suspect with a gun is out of bullets. The “Shivers” skill can help give you a hunch as to where a culprit might be hiding. “Visual Calculus” can help reconstruct a crime scene. As I played through the 20-ish hours of Disco Elysium I tried to figure out what skills were under-utilized, hoping to max out the skills used more often, but I couldn’t find anything that was disposable. And while you don’t necessarily level-up in the game, you earn new skill points fairly often that you can use to improve your skillset.

There are a few tools to help max out your skills. The first are cigarettes, alcohol, and speed. These substances grant you a bonus to one of the four categories, based on what substance you’re taking. So if you’re having trouble with a physical challenge, a swig of beer might help. Or a cigarette can help give you a boost to analyzing a crime scene. However, while these substances provide bonuses, they also damage your health and moral meter. These meters can also take damage through combat and dialogue, so you’ll need to find healing supplements to keep from dying or falling into an endless pit of despair.

You can also get bonuses to your skills by the clothes you wear. Much like equipping armor can grant you bonuses in a fantasy RPG, in Disco Elysium, your shirt, glasses, coat, and hat can give bonuses to your skills.

It’s nice to see ZA/UM playing to their strengths here. It turns Disco Elysium into more of an adventure game than what you might think of as a traditional cRPG. Still, there are times when the design misses a beat. Like many cRPGs sometimes dialogue options or resolutions to quests can get buried under branches of dialogue. After completing a side quest for a witness, I couldn’t figure out how to get her to tell me the information I needed, which led to me revealing information I would have rather kept secret as I just tried to find the right dialogue option. This doesn’t happen often enough to be a significant knock against the game, but when Disco Elysium is obsessed with dialogue as a mechanic, it stands out a bit more than in other cRPGs. There are also a couple of objectives that have some vague rules. So there are issues, but they aren’t numerous.

The game is technically sound. Again, the cRPG aesthetic doesn’t offer too much challenge, but with quest-heavy games like this, there’s always an opportunity for things to get buggy and Disco Elysium doesn’t have those problems. There’s also a lot of transitioning between interior and exterior locations that are done with quick loading screens. I really don’t have much to complain about.

In many ways, Disco Elysium feels like the game the cRPG genre needed. It’s been nice to see the genre return and while I can get tired of reading endless paragraphs and made-up history, I do love clicking through trees of dialogue, getting to know a character. The nature of this genre plays to the strengths of a detective story, allowing you to interact with the world through specific clues and conversations. And ZA/UM has taken it a step further by building a whole skill system to help explain how you interact with the world. It’s a smart idea, but it’d be nothing without the wonderful characters and intriguing mystery that propels you through the game. Disco Elysium reinvents the rules for the cRPG and I’m sure anyone making this kind of game right now is taking notice.